Alberdi Makila

The makila is not just a walking stick: it's a symbol deeply rooted in Basque identity. Traditionally used as a support for travel and as an instrument of defense, the makila has evolved to become a ceremonial object imbued with respect, hierarchy, and cultural pride.

Its artisanal production requires skill, patience, and knowledge passed down from generation to generation. Each makila is unique, and the manufacturing process can take up to a decade, from the moment the loquat is selected to the assembly of its finest details.

This piece represents the essence of the Basque people: strength, resilience, and understated elegance.

Today, Beñat Alberdi, leader of this third generation of makila artisans, along with his sister Saioa, tells us more about his life and work:

Hi Beñat, how did you get started in the trade?

My first contact with the craft was when I was a teenager. Every time I asked my father for some extra money, he invited me to work in the workshop to earn some money. So, I learned the trade and developed my interest in craftsmanship.

Can you summarize the creative process of a makila?

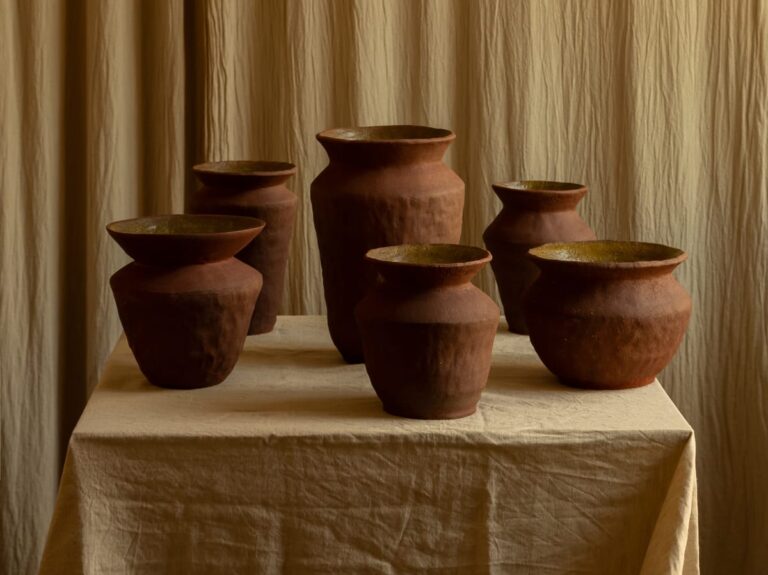

Summarizing the makila-making process isn't easy, as it involves multiple stages and artisanal techniques. But, to simplify, we could divide it into three main areas: woodworking, metalworking, and leatherworking.

It all begins in the forest, in spring, when we score the wild loquat branches to form the reliefs that will give each makila its unique character. The wood is cut in winter, and from there, a long process begins: it is stripped of its bark, straightened by applying heat, and left to dry for years, sometimes up to a decade.

Once finished, a finely hand-chiseled brass, nickel silver, or silver ferrule with Basque motifs is added to the lower part. The handle, made of horn and hand-braided leather, finishes the upper part. In honorary makilas, this handle is made entirely of silver or nickel silver.

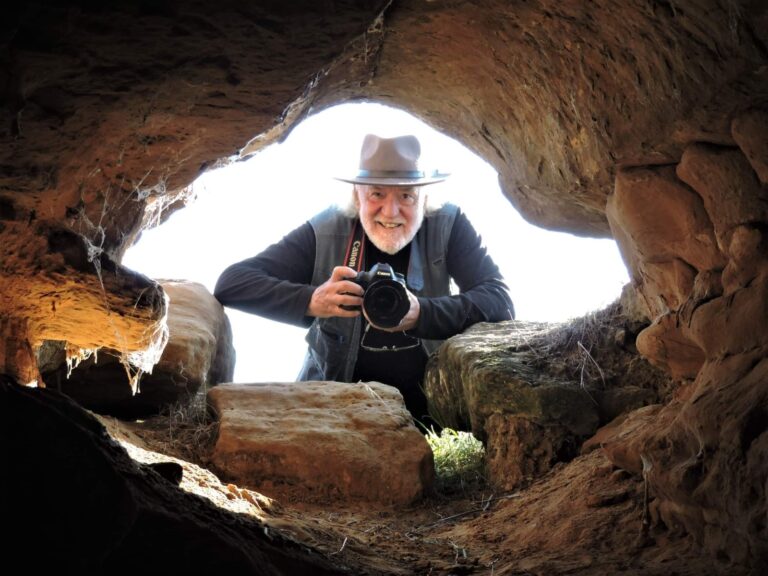

Do you have any hobbies outside of work?

Yes, I love nature and outdoor activities, especially surfing.

If you hadn't been an artisan, what profession would you have pursued?

Before dedicating myself to crafts, I worked as a salesperson for a multinational company, and I truly enjoyed what I did. Traveling the world was always something that attracted me. However, over time, I felt I couldn't pass up the opportunity to continue the family trade and become the third generation to make a living from craftsmanship. It was a decision that connected me to my roots and to something much deeper than a simple professional career.

The makila has been given to important figures as a symbol of honor and recognition. Do you have any special memories of any of those people?

That's a question I'm often asked, and the truth is, I couldn't single out just one person. For me, every makila I make is special. It's a piece that is rarely bought for oneself; it's usually given as a gift, and that gives it a very symbolic value, since you have to deserve it. Behind each order there is usually a beautiful story, full of emotion and meaning. Often, customers are moved when they come to pick it up, thinking about the reaction of the person who will receive it. It's an honor to be part of those moments.

What do the phrases inscribed on the handle mean, and how are they chosen?

Each customer can choose a personalized phrase to be engraved on the handle, something that has a special meaning and connects with the person who will receive the makila. There are traditional inscriptions that are still very present, such as Hitza Hitz ('The word is the word'), an expression that reflects the value of being a person of one's word, something deeply rooted in Basque culture. Another very common one is 'Nere bideko laguna' ('My companion on the journey'), which is usually chosen when a group of friends gives a makila to someone who is retiring, as a token of gratitude for their camaraderie and to remind them that they will always be part of the group.

Do you have a favorite place in the Basque Country?

Many, but if I have to choose one, I would say Txingudi Bay. It is a place of great natural beauty, where the sea, wetlands, and mountains coexist in perfect harmony. It is also right on the border between Spain and France, which gives it a very strong symbolic value. It is a meeting point for cultures, languages, and ways of life. We live at that crossroads, and I think that blend is also reflected in our work as artisans: we respect tradition, but with an open view of the world.

Our previous guest, Franz Frichard, left this question for the next one: Which island would you take with you to a 'deserted book'?

I would take the island of Bali from twenty years ago.

As a creator, do you have a place, person, smell, or belief that inspires you daily?

The sea has always been a constant source of inspiration for me, and it still is. Its strength, calm, and immensity connect me to something deep and essential.

How do you see traditional craftsmanship in the future?

I see craftsmanship as a living thing in the future, and that alone seems like a lot to me. However, I think the number of artisans will decrease considerably, which will make this craft even more unique and exclusive than it already is. This will likely make craftsmanship a product closer to luxury, not only because of its quality, but also because of the value it represents: time, know-how, and authenticity.

Do you have any opinions on AI?

Although it may seem far removed from our profession, the truth is that, for better or worse, today it is essential to be present in the digital world: social media, websites, online platforms... Everything is part of how we make ourselves known. Whether you like it or not, we have to learn to live with this famous AI, adapt, and find a way to integrate it without losing our essence.

Could you leave us a random question for the next guest?

Yes, what inspired you to start creating your products by hand, and how has your process evolved since then?