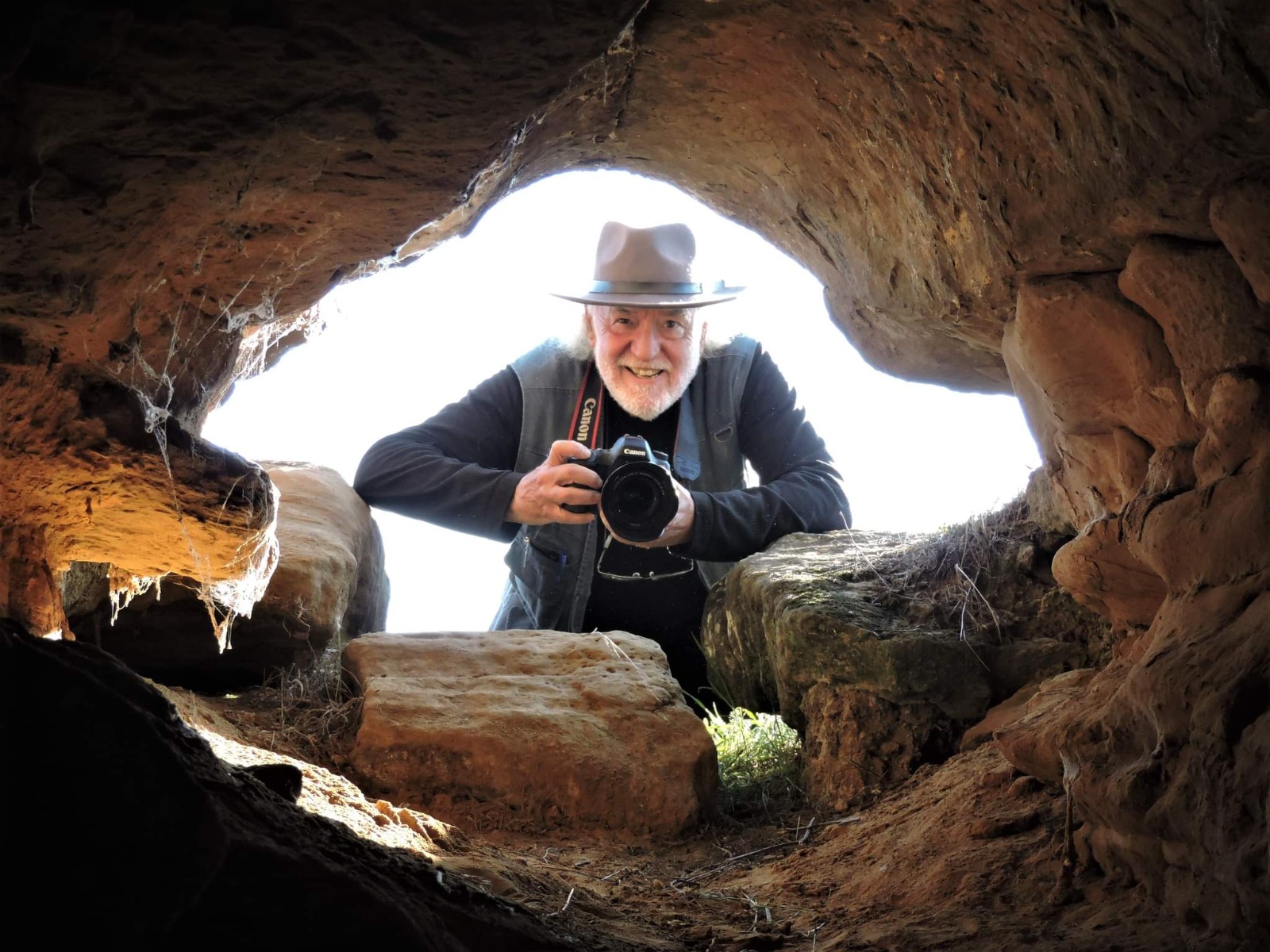

Eugenio Monesma

A little introduction is needed. A thick beard, a fedora, a safari vest, a camera at the ready, and clear ideas. More than four decades ago, this Aragonese filmmaker began to travel through the Spanish regions to leave a graphic record of the trades and traditions that still existed and were being lost in our country: clothing, instruments, construction and architecture, agriculture and harvesting, crafts, gastronomy, festivals and rituals, legends and customs... and so on, up to more than three thousand documentaries that today represent one of the most extensive and important ethnographic archives in Spain.

Seeing and hearing his recordings, starring real people, jobs, and languages, is like traveling to the friendly artisan past that preceded us. A not-so-distant past that is now integrated and preserved in the most advanced of the present, since social networks and online dissemination channels ensure that this video material, now digitized, has millions of followers and views all over the planet.

The author himself, Eugenio Monesma, tells us in these lines more about his life and the last forty years of work teaching important parts of the idiosyncrasy of a country:

Hello Eugenio. You must have traveled many kilometers. Have you managed to visit all the provinces of Spain?

I haven't managed to visit all of them, although I have very few left. However, I can say that I have visited almost all of the towns in Aragon. It has been many miles driving, I like to drive. I am currently still on the road, recording my Canal Cocina series, “Los Fogones Tradicionales”.

Do you remember your first camera or technical recording equipment?

Yes, it was a Super-8, model Eumig 860, which I bought in 1979. Then I evolved with the introduction of video, so there have been quite a few models and formats that I have used up to now. When I could afford it, I tried to improve my cameras and equipment, and therefore the quality of the recording.

After seeing the content of many of your documentaries, can you tell us how important the words “sustainability” and “ecology” are for you?

Son palabras cuyo sentido se aplica pocas veces a la Naturaleza. La sostenibilidad es baldía si se elimina el ganado que limpia los montes, si las aldeas se deshabitan y amplios territorios se quedan abandonados. Nuestros antepasados supieron aprovechar inteligentemente todos los recursos que les daba la Naturaleza para sobrevivir.

Do you have a favorite spot in Aragon?

Many, because in this land we have all kinds of landscapes, from high peaks in the Pyrenees to desert areas in Monegros. But there is a town that I have a special affection for, San Juan de Plan, in the Pyrenean valley of Chistau (Huesca), where its people have shown me their knowledge about the use of resources. There I have been able to record documentaries such as wool, homemade soap, grass harvesting, hemp cultivation, laundry in the river, and many more. In addition, the protagonists of these documentaries, such as Aunt Serena, Anita, and Josefina, went from being artisans in front of the camera to being family friends.

Where do you feel most comfortable within the production processes of a documentary piece?

Especially in the treatment and coexistence with the protagonists. Sharing walks and stays in the mountains with the transhumant shepherds and their flocks, or participating for a few days with the lime makers, charcoal makers, tile makers, and other experts while they showed me their work was enriching, both on a human and cultural level. This coexistence sometimes lasted more than eight uninterrupted days with them and allowed me to experience everything firsthand, sharing friendships with many families from our villages.

Is there any documentary that was the most difficult for you to film?

The most complicated were those that were recorded in the mountains - grazing, gypsum, lime, tile, coal cooking ovens, the navatas... - because we depended on the weather. But other documentaries required several trips to be able to record the entire process, such as the cultivation of flax, hemp, spelt, etc., or the manufacture of carts, for which I needed two months to film.

You have compiled a hundred trades to remember in your next book which will be released in October. Among them, do you miss any specific traditional trade that has already been definitively lost?

Sí que hay algunos oficios que echo de menos y que, durante la preparación del libro “100 oficios para el recuerdo”, me han traído agradables recuerdos, pero nostalgia por su pérdida. Uno de ellos es el del batihoja, el trabajo de convertir una pequeña pieza de oro en cientos de finísimas láminas de pan de oro para de decoración de retablos y las figuras religiosas. Este lo grabé en un pequeño taller de Madrid, que llevaba muchas décadas dedicado al oficio, y que un año después de terminar el documental tuvo que cerrar por no poder competir, ya que se importaba de Alemania el pan de oro laminado industrialmente.

What historical figure would you have liked to accompany you on one of your shoots or to make a documentary about him?

Rather than historical figures, if we talk about those who have governed the people, I would prefer to share my time with those who have contributed knowledge to humanity, such as Leonardo, Galileo, etc. But I would feel more comfortable, as I have demonstrated throughout my life, learning from those peasants who tried hard to support their families in the difficult times they had to live through.

You have received awards, prizes, and medals. To what extent is public recognition of your work important to you over the years?

In the first years of making documentaries, the awards were very important, both because they made my work known and because of the financial amount they meant to be able to buy the material I needed. Nowadays, I understand that the recognitions are like approval of a job well done throughout my professional career, but, above all, an act of gratitude to all those people who contributed their knowledge to the documentaries.

Your content is seen and “hooks” all audiences and ages, right? Where have the comments, congratulations, or more distant criticisms come from?

When I started uploading my content to YouTube and social networks, I thought that it would only interest people over fifty, but I was wrong. I am surprised that many of the comments I respond to every day come from young people in their twenties who show interest in all this recent past that has been lost. But what draws my attention the most is that, through social networks, I am reaching all corners of the world, from Latin American countries where my documentaries are very grateful, to the United States, and many countries in Europe or Asia. It was unthinkable when I produced the documentaries.

Our previous protagonist, Ángel Peralta, left a question for the next guest. It is this: What do you enjoy the most in your daily life?

If I am not going out into the mountains in search of ritual and functional stones, or I am on a trip filming Los Fogones Tradicionales, what I enjoy the most is being able to carry on with my normal pace of life. The first phase of activity is early in the morning, my hour of swimming, continuing to work, and then having a quiet meal with my wife. In the afternoon I continue writing, reading, and having dinner.

If today you were with a teenager watching some of your documentaries on traditional occupations, what would you tell him?

In this consumer society where everything is thrown away without being used, I would try to convey to him that he should understand that, in the past, life was simple, that any object, however simple, had a use and a lot of work behind it. That nothing was thrown away and that our way of life had a direct relationship with Nature.

Can I ask you to leave a question for the next guest?

Sure. To what extent is your life linked to the natural world that surrounds us?